Americans have a special affinity for our vehicles.

As crazy as it sounds, nearly 2/3 of Americans “love” the the time they spend in their car according to a Cars.com survey. Many of us listen to podcasts or audiobooks on our daily commutes. Alternatively, some of us just enjoy the solitude, peace, and quietness.

In a way, our cars are like a mobile sanctuary. And for good reasons…

Vehicles today come loaded with technology. Whether it’s Bluetooth connectivity, XM Radio, or even TV screens, the vehicles we drive today are luxurious compared to the “top of the line” just a few decades ago.

However, all this added technology and progress comes at a price.

While wages for the average American have stagnated over the past decades, the price of vehicles continue to rise. Therefore, we’re spending a much greater percentage of our disposable income on our transportation needs.

New car sales in the United States

According to CNBC, the average new car sold in 2019 hovered around $40,000 including add-ons. This is a nearly $10,000 increase when compared to just a decade earlier.

Coupled with stagnant real wage gains for Americans over the same period, the cost of vehicle ownership is becoming increasingly burdensome.

With the median household income ~ $60,000, vehicles often comprise 50%-100% of American’s annual wages.

Perhaps, this is why the average new car is financed over 72 to 84 months. As a kicker, the average annual percentage rate (APR) charged on a new car loan is 6.4%.

While Americans may be able to afford the monthly payment, that does not necessarily mean that financing that car is a good decision.

100% down vs. financing your car purchase

Realistically, there’s only two ways to buy a vehicle. You can either plunk down the full cost up front or pay for the car overtime.

Obviously, there’s pros and cons to each choice.

If you pay 100% down, you miss out on the “opportunity cost” of that money. Instead, that money could be invested and more than likely earn a higher rate of return. In many cases, this would more than make up for the interest charged (as long as your interest rate isn’t more than 6%+).

For instance, you could contribute to a 401(k) plan with an employer match with the money used to purchase the vehicle. Your contributions would allow you to realize a 100% return (on the matched dollars). As an added bonus, the market generally appreciates over time, so your contributions would continue to grow.

If you contribute to a Traditional 401(k) or IRA, or even a Health Savings Account (HSA), you could receive a tax deduction that offsets the interest on your loan.

Even though the numbers may work in your favor, that doesn’t necessarily mean borrowing on your car is the best choice. After all, few people have the discipline to actually invest the excess.

Let’s explore further.

Borrowing comes at a hidden cost (and I’m not talking about interest)

Have you ever been out to lunch or dinner with your boss? More than likely, you’ve scanned the menu from right to left, letting the prices guide your decision.

Suddenly, your boss says, “Don’t worry about the check. It’s on the company.” Now that you no longer have to pick up the tab, your eyes (and stomach) begin wandering to those pricier items. Perhaps, you’ll indulge in the surf and turf or filet.

The point is your budget is much more strict when you feel the burden of the actual expense.

Similarly, financing a new car can have the same effect.

Financing a car has the potential to allow you to drive off the lot with a vehicle you could not otherwise reasonably afford. This is how people end up driving cars that are worth 50%-100% of their annual income. Sure, they’ll be putting ~10% of their income towards the loan each year for the next 6-8 years. In the moment, they’ll feel like they deserve the luxury. However, when the newness wears off, they’ll still be left with the payment.

Clearly, just because they could make that more expensive vehicle work in their monthly budget does not mean it was the best choice.

The dealership WANTS you to finance

For the dealership, the fact that they can sell you a car with a larger sticker price is a huge incentive to “help you” get into that new car by financing your purchase.

Will they make money on the interest from the loan? Sure! However, the real incentive is to SELL you a more expensive car.

Even if they earn at 0% interest, they still come out ahead if they can put you in a vehicle $15,000-$20,000 more than you would have bought WITHOUT financing. After all, their parts, service, and extended warranty departments are the real cash cows.

For many car buyers, the issue isn’t necessarily whether they pay 100% down or 20% down and finance the rest. The key point is the TOTAL COST of the vehicle and how that measures up to what you can actually afford.

For this reason, the best strategy is probably to buy a car you CAN pay for in cash or save up for in 1-2 years. For most, this comes out to less than 50% of their annual income.

As we all know, cars go down in value. Instead of driving that luxury car today, why not invest and drive whatever you want in the future without a financial hangover?

The negatives of financing vehicles

Most blanket financial advice you’ll hear or read says you should avoid the trap of financing your next vehicle purchase. For most Americans, this is sound general advice.

For the most part, paying cash for a vehicle keeps you from spending too much on your next purchase. It keeps you within an allotted budget.

While you’re able to “play and pay later” when you finance the vehicle, eventually, the loan must be repaid even though the new car smell is far gone.

Aside from putting you in too much car, financing that new vehicle poses 3 broad issues that we’ll discuss:

- The monthly payment imposes “risk” by hindering your monthly cash flow

- Your financed vehicle is worth less every month

- Debt acts as leverage and magnifies the outcome

1. Financing a vehicle constrains your monthly cash flow and introduces risk

So, you’ve decide to finance that vehicle purchase.

While you’re able to drive off the lot as if you own your vehicle outright, the financing department holds title to your vehicle as securitization. In the event you default on your monthly payments, they have every right to repossess your car, sell it, and sue you for any remaining amount on the loan.

Sounds scary right?

If you’re unable to make the payments because of a job loss, extended illness, or other poor financial decisions, you can certainly find yourself in a precarious situation.

Borrowing money for your vehicle purchase introduces “risk.” For some, this risk is hardly noticeable. Perhaps, you have ample cash in the bank or liquid investments. More than likely, you could sustain the payments and lifestyle until you get back on your feet.

For others, the risk is way greater than they realize. After all, many Americans live paycheck to paycheck. In the event of a job loss, they may only have a month or two before defaulting on their car, mortgage, or credit cards.

Payments inhibit your monthly cash flow

While you may be able to enjoy your car today, you’ll be paying for it tomorrow (and the next day… and the next day…)

In a way, you’re agreeing to a pay cut for the next several years when you finance a new car purchase.

For example, let’s say your monthly payment is $500 per month for the next 5 years. By using simple math, you’ll be spending $6,000 per year on the vehicle. If you’re making $50,000 per year, would you take a $7,500 pay cut (which includes taxes) for the next 5 years to drive that car?

When you re-phrase it that way, the decision probably becomes much harder. However, this could offer a different perspective that influences your decision.

In the end, financing your car inhibits your monthly cash flow. For some, a $500+ car payment may not be noticeable and impact their lifestyle. However, for most of us, $500 per month can be the difference of breaking even in a given month.

Interest is a “penalty” you pay

Not only does the car payment rob you of monthly cash flow, you are also “penalized” in the form of interest payments.

With each monthly payment, only a portion will go to reduce the loan balance. The rest of the payment is financing income for the bank or financing department (at your expense). Each month, you’ll be charged interest on the remaining balance outstanding. Over the life of the loan, you could end up paying thousands of dollars in unnecessary interest.

With the average interest rate of over 6%, this is nearly the return you could expect from the relative risk of investing in the stock market over the same period.

Clearly, this makes that car purchase much more expensive than the original sticker price. Plus, earning a spread on your investment becomes increasingly unlikely given the risk you assume.

2. Your car depreciates in value

Unless you’re buying collector cars or vehicles you plan to restore, your car will be worth less with each passing year.

Eventually, that once new, prized possession will be seen for what it really is: a hunk of metal and scrap parts.

This phenomena is called depreciation.

The amount of depreciation is determined by a few factors. However, as in any market economy, supply and demand plays a key role.

The demand for new vehicles is pretty high. With a new vehicle, there shouldn’t be any underlying or unforeseen issues caused by mileage. If issues arise, they are probably covered by the manufacturer’s warranty. Further, manufacturers and dealerships spend millions in advertising every year to influence consumers decision. Through their market research, they know how to present their product to make it hard to resist for the average person.

When buying a new car, there are no scratches, dents, wear, and tear. Plus, that new leather smell is hard to resist. Because the car is brand new, the useful life is longer. Therefore, brand new vehicles tend to be in higher demand. The intrinsic aspects of driving off the lot in a new car also contributes to the higher selling prices.

However, once the car is driven off the lot and the first few miles are added to the speedometer, the value attributable to these intrinsic traits suddenly disappear.

You no longer own a “new” car within mere minutes of driving out of the dealership parking lot.

How depreciation impacts your car’s value

According to Carfax, new cars drop ~10% just in the first month of ownership.

This means if you buy a $40,000 vehicle, after only one month, the car is suddenly worth only $36,000 (on average). For many, this $4,000 unrealized loss in value is more than they make in a month! It’s hard to build wealth when your assets are depreciating enough to offset your income.

In the first year, the average vehicle is worth only 80% of the original price. After just a single year of ownership (and ~10,000 miles driven), that $40,000 car is only worth $32,000. On average, this means your vehicle dropped by $667 per month.

Each year, the average new car will continue to drop ~10% until it’s worth just the price of scrap.

If your car is a substantial part of your total assets or income, it’s hard to build wealth with such negative returns.

3. Financing a vehicle leverages these negative returns

At first, you may be thinking what does depreciation and my car’s loss in value have to do with whether I should finance a car or not?

Well, debt acts as leverage. In turn, leverage amplifies and magnifies the outcome of financial choices.

Therefore, leverage can be good or bad.

An example of “good” leverage

For the most part, home-ownership and real estate is the quintessential example of what’s considered “good debt.”

As an example, a home mortgage is generally good leverage. With just 20% down, a homeowner has the ability to control 100% of the asset that generally appreciates each year with the housing market. Therefore, their equity value increases as the principle balance of the loan is paid down AND as the property value increases.

“Bad debt” presents an alternative outcome

However, with a depreciating asset, the story drastically changes.

When the value of the leveraged asset is increasing in value, all is good as the gains are magnified. However, if the asset depreciates or decreases in value, the loss is amplified.

If the asset value falls below what is owed, the result is “negative equity.” Not only is the car worth less, new car owners who finance the purchase still have to pay down the loan plus interest.

Because vehicles depreciate so quickly, the decrease in value often outpaces the amount paid down on the loan. This often results in more being owed on the car than the vehicle is actually worth.

Let’s look at an example

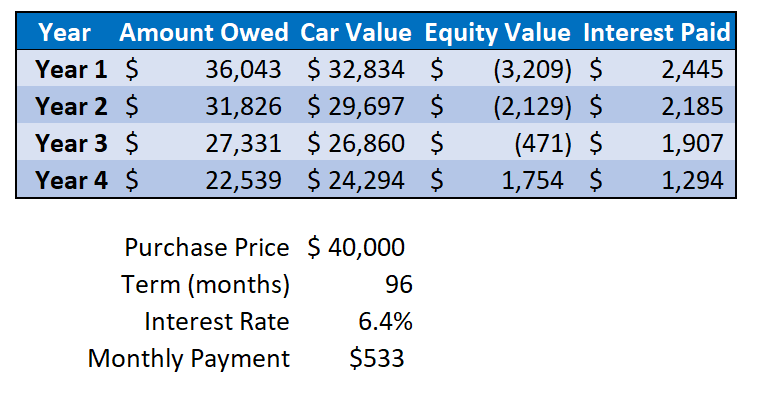

As we’ve previously discussed, the average new car purchase price is nearly $40,000 including ad-ons. While average loan terms vary anywhere for 7-9 years, I’ve selected 9 years to arrive at a monthly payment that tends to be more affordable (~$533/month).

With an average interest rate of 6.4%, the total interest paid over the life of the loan will be over $11,200. Therefore, the total cost of the vehicle plus financing arrives at over $51,000.

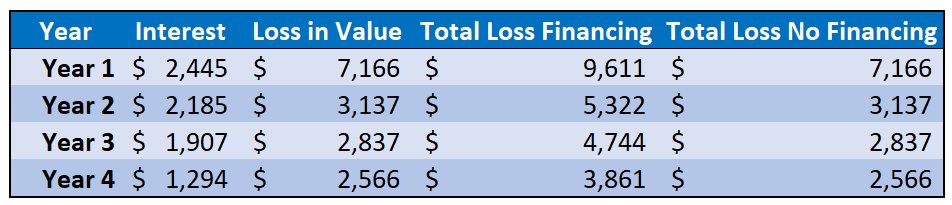

Not only will borrowers pay interest of nearly $2,500 in Year 1, $2,100 in Year 2, $1,900 in Year 3, and $1,300 in Year 4, the vehicle depreciates the most in value during these early years.

Often, this leads to “negative equity value” because the loss in value of the vehicle may exceed the principle paid down on the loan.

Annual Analysis

In Year 1, the average vehicle drops from $40,000 to just under $33,000. This is because the average new car declines 10% within the first month of driving off the lot. Plus, vehicles generally depreciate ~10% annually. Therefore, Year 1 can represent the greatest loss in value for new car buyers.

In fact, the total depreciation and interest in Year 1 is nearly a $9,500 hit to an average car buyer’s net worth.

At the end of Year 1, this borrower owes more on the loan than the car is actually worth because of the accelerated depreciation in the first year. After 12 months, they have negative equity of ~$3,209.

But, what does this mean?

The concept of “negative equity” can be difficult to understand at first. However, in practice, it’s pretty clear.

If this buyer were forced to sell the vehicle, they would end up OWING this amount AND have no vehicle to drive. Therefore, this buyer would be “underwater.”

In Year 2, the economics begin improving (slightly). As the principle on the loan is paid down, the interest begins decreasing. The depreciation tapers to ~10%/year or ~.83%/month. Slowly, the principle payments begin catching up with the market value of the car.

After Year 3, we’re starting to break-even. While the car buyer in this example still owes more than the car is worth, we’re pretty close to even. If they were forced to sell the car, they would only be out of pocket a few hundred bucks.

After 4 years of payments, we’ve finally gotten enough traction in the principle payments to outpace the loss in value. Now, we actually have an asset that is worth more than the car loan. Therefore, we now have “equity” in the vehicle.

What if you paid cash?

The economics certainly change when there’s no debt associated with a depreciating asset.

If you paid for the vehicle in full in Year 1, there would be no risk of negative equity. Plus, there would be no interest charged since there wouldn’t be any loans involved.

Since the depreciation is unavoidable, this would be the main source of loss. However, by paying cash, a buyer would avoid ~$2,000/year in annual interest.

As previously mentioned, over the course of the loan, a cash buyer would save over $11,000. This represents a nearly 20% savings on the total cost of the vehicle.

So, should you finance a new car purchase?

For most Americans, financing a new car doesn’t make a ton of sense.

Could you theoretically earn a higher interest rate on your investments? Absolutely. However, in practice, most of us are unable to maintain the discipline of investing any excess.

While most Americans should put down as much as possible (or pay 100% down) in cash, there are a few instances where financing the car makes sense.

Extremely low interest rates may provide more efficient alternatives

If you’re able to secure a 2-4 year loan at sub-3%, you more than likely could allocate more of your capital to better opportunities.

For instance, maybe you have substantial credit card debt. If you “need” a newer vehicle and have managed to save up cash, this money is probably better deployed on the credit card balances with 15%+ APR. This presents a guaranteed, double-digit rate of return.

(Note: If you have substantial credit card, you’re probably best waiting to clean up your act before buying a vehicle. This is just a hypothetical example to illustrate how your money could be better allocated to higher interest debt.)

Alternatively, perhaps your employer matches retirement contributions. Putting enough in your 401(k) to get the “free money” is another place to get double (or triple digit) guaranteed rates of return. Why miss out on this match just to save 2.2% in interest?

(Note: Hopefully, buying the car doesn’t keep you from being able to contribute to your retirement. If it does, the car may be out of your budget.)

Perhaps, you like the safety of having a substantial, liquid pile of cash in an emergency fund. Many high-yield savings accounts offer rates nearly as high as some car loans.

For example, I recently purchased “new” truck that was a model year older. Besides getting $10,000 off the MSRP, I was able to secure a 3-year, 2% loan. Instead of putting 100% down, I opted to open a high-yield savings account earning comparable interest. Essentially, this offsets the interest I pay while also allowing for liquidity.

Weighing the Pros and Cons

Deciding whether to finance your vehicle purchase or pay cash may not be as straight forward. After all, it depends on your tolerance for debt and where else you would spend the money.

For many who enjoy investing, they will probably earn a higher rate of return by investing in the market. However, there is always an element of risk with this strategy as the market may decline in any 1-5 year span. Plus, most Americans don’t have the kind of discipline it takes to keep from spending the money on other consumer purchases.

Personally, I do not like owing money. Therefore, I’ve made the conscious choice to max out my “guaranteed” rates of return and pay down the loan faster.

For instance, I allocate enough in my 401(k) to get 100% of my employer match. I max out my Health Savings Account which provides a ~20%-25% guaranteed rate of return (from taxes) as well as investment appreciation. I hold enough in my high-yield emergency fund to sustain my bills and lifestyle for ~4.5 months. The interest rate earned practically offsets the interest paid on the loan.

With any extra each month, I apply to the loan so that I can free up the principle payments earlier.

Find your sweetspot

For the average American, avoid car loans at all costs. This build discipline and helps ensure your financial priorities are in order.

Unfortunately, most Americans simply do not have the net worth or excess monthly cash flow to comfortably live the life they want, save for their future, and drive a new car on payments. You don’t want a car to get in the way of the life you want to live today and the dream you can achieve tomorrow.

However, if you do decide to borrow on your next car purchase, there’s probably a “sweet spot” for how much fits into your financial picture. You’ll need to decide for yourself how much is “too much” car and where the money can be best allocated to maximize your net worth.

After all, the choice of whether to finance a car is not cut and dry. There are certainly pros and cons with financing and paying cash for your next car purchase.